Any movie having Stanley Kubrick’s name on it has a legendary status in the industry. Due in large part to the polemic nature of his films, Kubrick is regarded as one of history’s most important directors. Therefore, it is not surprising that “A Clockwork Orange,” which likewise requires the most caution, continues to be one of his most well-regarded movies. Kubrick uses violent portrayals of sexual violence, suicide, and psychological torment to create a movie with profoundly moving ideas about free will, government, and ethics.

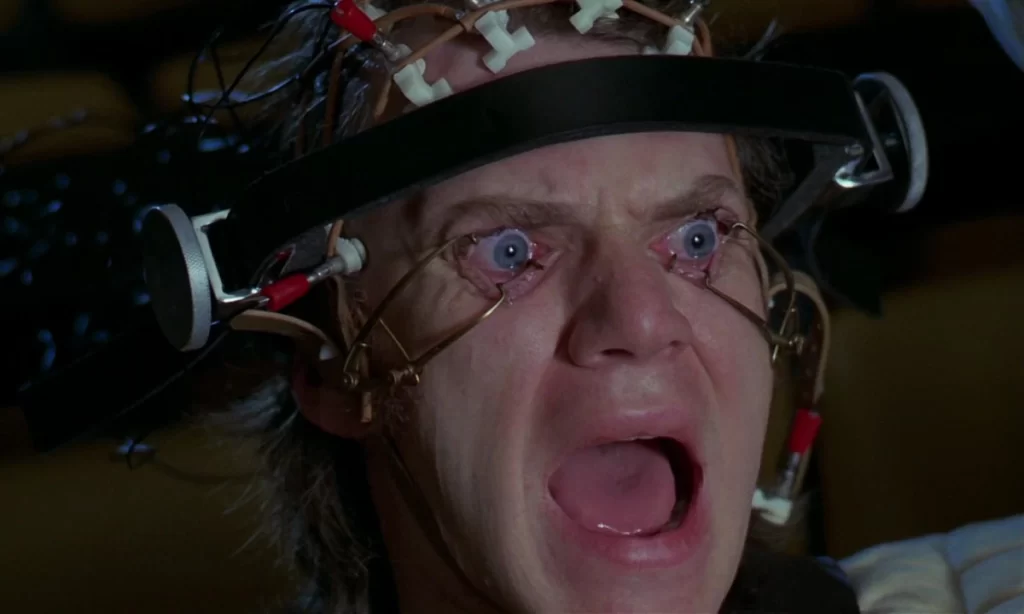

The condition-reflex therapy Alex receives in the movie, which includes subconscious torment and brainwashing, rarely attempts true rehabilitation and instead tends to the illusion of normality while ignoring the complexity of the human condition.

One must examine the relationship between Burgess’ book and Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation in order to comprehend A Clockwork Orange’s conclusion. As it overlooks the 21st chapter, which is crucial to Alex DeLarge’s salvation and integration into social norms, the movie obscures Burgess’ genuine literary aims. Although many believe Burgess’ climax to be weak and out of keeping with the tone and spirit of the novel, viewers have accepted the film’s gloomy and complex ending as the more realistic one.

A Clockwork Orange: Key Takeaways From The Movie

A Clockwork Orange delves deeply into the moral and ethical conundrums raised by the issue of free will and choice. Alex (Malcolm McDowell), a criminal who lives on the periphery of society’s norms, is mostly predisposed to drugs, instability, and graphic violence from the beginning of the story. This gives him a great deal of excitement, which gradually starts to wear on him during his recovery program, which features psychological torture and unethical forms of coercion. Is Alex, with his proclivity for moral and sexual perversion, more true to his humanity than when he appears to have been transformed by the forced reconditioning of the Ludovico treatment? This is the key question that is put forward in the movie.

The narrative centers on Alex DeLarge, a young offender is living in a dystopian Britain. Alex is the leader of a group of five criminals, including himself, who frequently engage in different violent actions while high on drug-induced milk. It is quite evident from the outset that Alex DeLarge, like Patrick Bateman in American Psycho, is not just a monster but also a byproduct of his society.

In the movie, organizations of power and control, like the prison system and the psychiatric circle that promotes forced reformation in the name of scientific development, fight Alex’s belief that evil is a natural state that lives inside people. Because the System denies Alex meaningful choice and intrudes on his freedom, it directly challenges his concept of self or Autarkia. Alex represents the conflict between free choice and the powers of control, power, and change that conceal their own shady underbelly when seen through this specific lens.

A Clockwork Orange Ending: How Is The Movie’s Ending Different From The Book?

Alex’s good behavior is manufactured and not the consequence of an actual transformation in his morality is closely related to “A Clockwork Orange’s” other central theme, which is the willingness of the state to use its people for its ends. The prison sells Alex’s transformation as scientific progress to the public after the excellent physicians have finally finished torturing him into quiet acquiescence. Despite the fact that Alex isn’t properly healed, they see it as a novel and compassionate approach to rehab, and they really don’t even care what happens to him after he goes.

A societal reflection on the entire film is another idea worth talking about. There are striking similarities between the brutality of street gangs and lab workers. Moreover, the cops later hire two of Alex’s gang members. This supports two important theories, a field that naturally leans toward violence requires workers who share that tendency. The primary distinction here is whether they will be employed by the government or the business world as delinquents.

Similar to Kubrick’s alterations to Stephen King’s The Shining, A Clockwork Orange closes on a debatable note that vastly deviates from the conclusion of the original book. In contrast to Burgess’ Alex, who is a victim of the state, Kubrick’s Alex participates in the state’s schemes by agreeing to comply with restrictions in return for engaging in socially acceptable transgression.

“A Clockwork Orange” has a gratifying yet unpleasant ending. Alex is not a person whose freedom to cause mayhem should be applauded, despite our sympathies. At the same time, those deserving of compassion are overlooked. Only Alex and the corrupt officials he now work for profit; the victims Alex tormented and killed receive no compensation for their suffering.