Restoring and rewilding landscapes often involves the reintroduction of species, but what happens when the desired species no longer exists? This is the dilemma faced in the case of the Aurochs (Bos primigenius), the wild ancestor of modern cattle, which hasn’t been seen since the last individual died in 1627 in Poland.

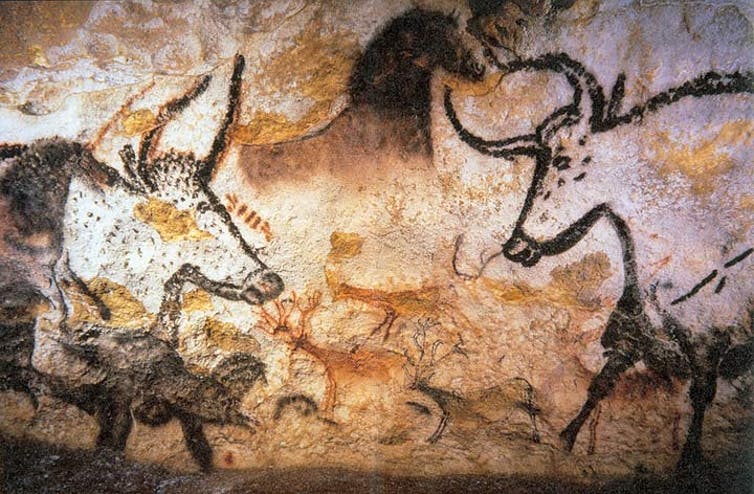

Aurochs, depicted in cave art and deeply ingrained in human history, faced extinction due to the advent of agriculture and domestication.

Despite their historical significance, efforts to revive the Aurochs are underway, relying on the concept of back-breeding. This involves breeding descendants of the Aurochs, selecting those displaying Aurochs-like traits to eventually recreate a similar animal.

Reviving the Extinct Aurochs in the Pursuit of Restoring Ancient Lands (Credits: Earth Touch News)

The first attempt to revive the Aurochs occurred in the 1930s with the creation of the Heck cattle by German zoo directors Lutz and Heinz Heck. However, the resulting Heck cattle, though not true Aurochs recreations, have found utility in pastures and zoos across Europe.

The Oostvaardersplassen nature reserve in the Netherlands employs Heck cattle to simulate “natural grazing,” supporting the idea that large animals like the Aurochs played a role in shaping the European landscape with their grazing behavior.

As rural land is abandoned due to urbanization, the push for reintroducing large grazers, descendants of the Aurochs, gains momentum. The hope is that these animals can help engineer a future European wilderness, reconquering lost lands.

Despite multiple attempts at back-breeding, there is no shared criteria guiding these projects toward a common goal. Genetic considerations play a role, but the first full Aurochs genome was only sequenced in 2015, leaving much to be understood about genetic variability.

The absence of a standard for what constitutes an Aurochs and ethical debates on the resurrection of extinct species lead to a future with competing Aurochs variants, driven by aesthetic preferences and differing visions of the past.