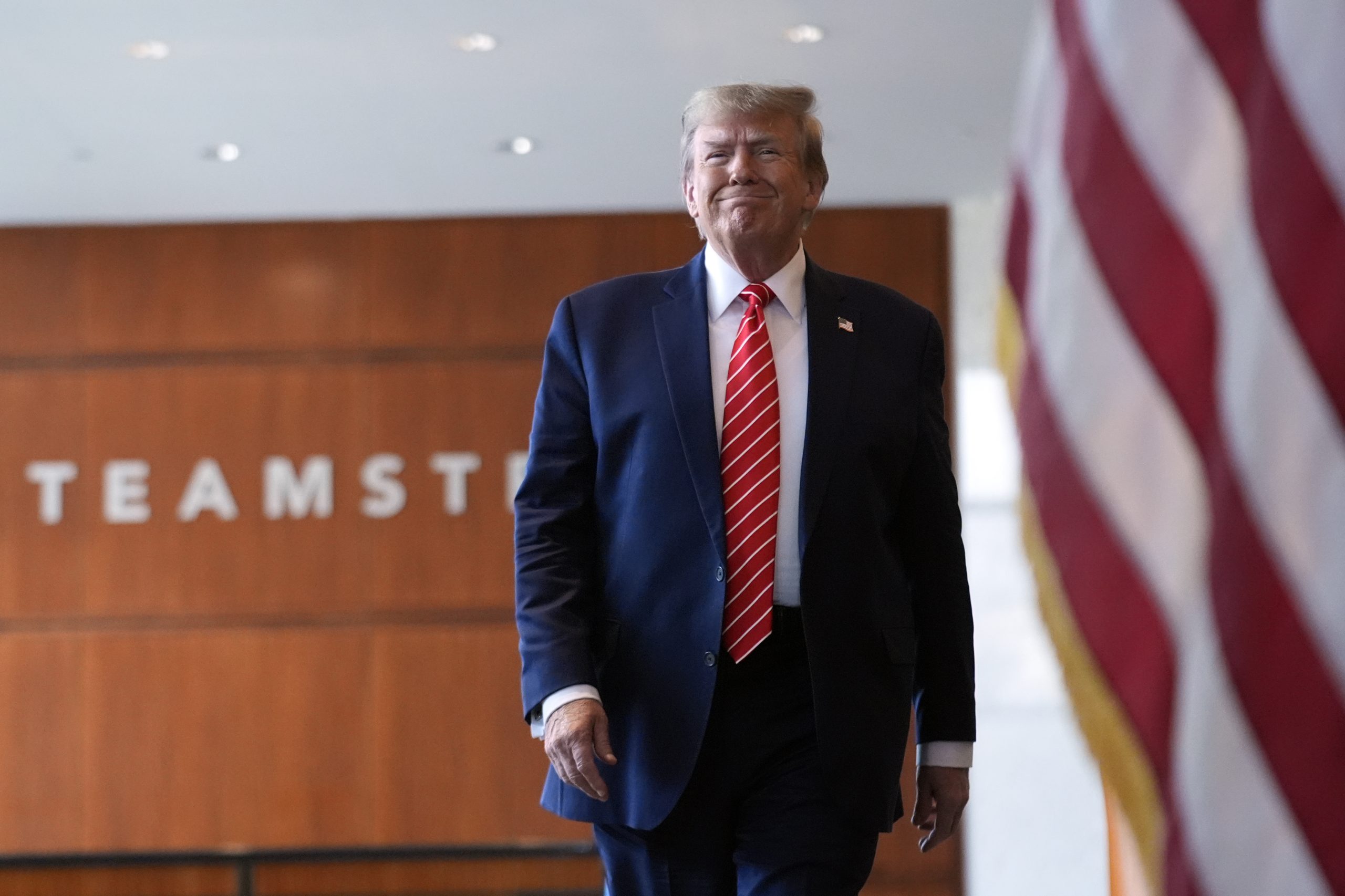

The Supreme Court justices are not typically regarded as historians. This became evident shortly after January 6 when historian Eric Foner suggested that invoking Section 3 of the 14th Amendment could serve as a mild punishment for Donald Trump’s actions during the Capitol insurrection.

Foner highlighted that applying Section 3 could be a quicker and simpler alternative to impeachment.

However, during the recent hearing on Trump v. Anderson, where the justices deliberated on whether a former president involved in an insurrection should be barred from seeking reelection under Section 3, historical considerations seemed to take a back seat.

Despite the significance of this case in shaping our understanding of the 14th Amendment, the focus appeared more on finding a way out of directly addressing Trump’s alleged role in the insurrection.

The hearing underscored the tension between upholding constitutional principles and the practical implications of applying them. The justices seemed wary of setting a precedent that could lead to the disqualification of candidates based on broad interpretations of “insurrection,” fearing it could trigger a cycle of retaliatory disqualifications in future elections.

The lawyer representing the group seeking Trump’s disqualification pointed out the rarity of invoking Section 3, emphasizing the exceptional nature of the events of January 6. However, some justices seemed hesitant to accept the clause’s self-executing nature, suggesting that congressional action might be necessary to enforce it effectively.

Even Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, known for her expertise in Reconstruction history, expressed doubts about whether Section 3 was intended to apply to presidential actions. She suggested that its primary purpose might have been to prevent former Confederate officials from holding state-level positions, rather than targeting the presidency specifically.