Astronomers found the new planet, HD 63433 d, using NASA’s TESS probe, which is short for Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite. The mission was designed to discover thousands of exoplanets in orbit around the brightest dwarf stars in space.

The scorched world is the smallest and closest known young exoplanet, at only 73 light-years away. Scientists estimate it’s about 400 million years old, a mere whippersnapper compared to our 4.5 billion-year-old home planet.

“Young terrestrial worlds are critical test beds to constrain prevailing theories of planetary formation and evolution,” the discoverers said in a new paper published in The Astronomical Journal.

There are now 5,569 exoplanets that have been confirmed, and over 10,000 more are being considered. From a statistical perspective, the increasing count barely touches the surface of planets that are thought to be in space. The universe probably contains many trillions of stars, given the hundreds of billions of galaxies it contains. Furthermore, if the majority of stars have one or more planets orbiting them, then there are an infinite amount of undiscovered worlds.

HD 63433 d is intriguing because one of its sides always faces its star. Furthermore, it is much closer to its star than Earth is to the sun. In fact, it’s eight times closer to its host star than Mercury is to the sun. That makes the exoplanet’s orbit so snug that its year is only four days long. As any experienced sunbather knows, if you don’t turn over, one side is going to get seriously burned.

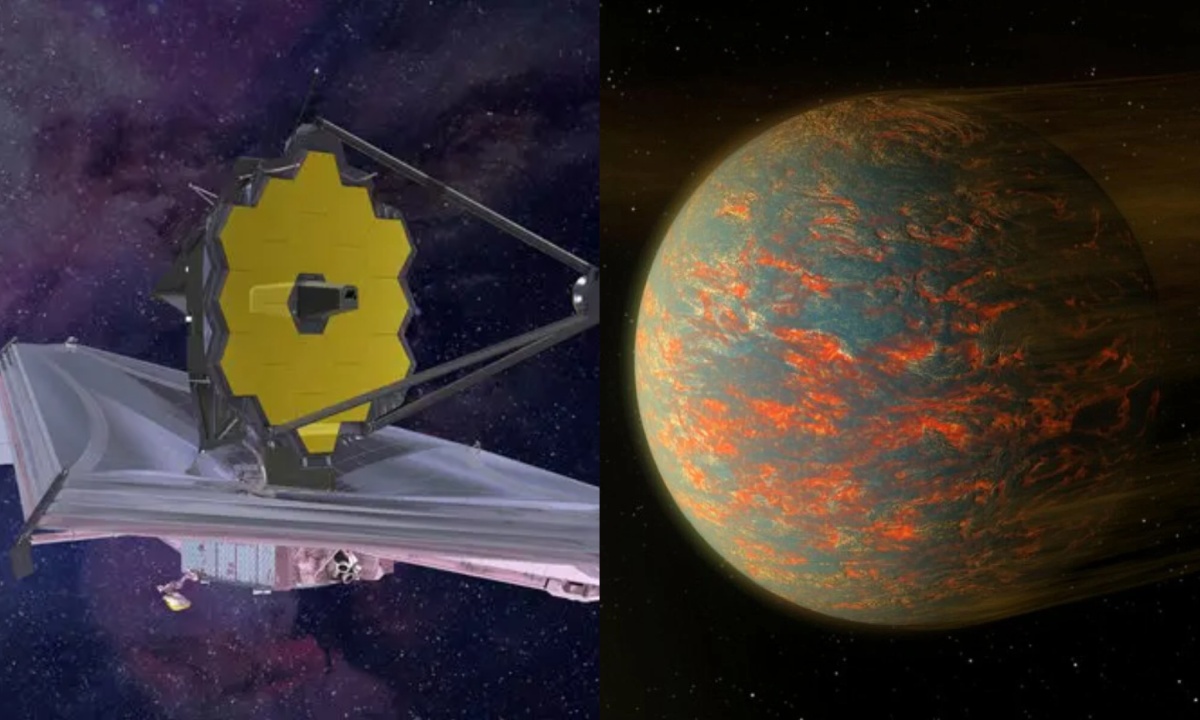

Astronomers believe the side facing the star is subjected to temperatures of about 2,300 degrees Fahrenheit. But the backside of the planet that never receives starlight is a mystery, something the research team hopes to learn more about in the future. The James Webb Space Telescope, the most powerful infrared telescope in the cosmos, could reveal more details about this young world, as well as search for hints of an atmosphere.

“Young planets are exciting because we can study how planets change over time by measuring their properties at different ages,” said Andrew Vanderburg, one of the co-authors, on X. “This is kind of like studying how humans age by observing a baby, a child, a teenager, and an adult, without waiting for the baby to grow up.”