Although the November presidential election is still more than nine months away, with only two states having voted and less than 1 percent of the electorate having cast a ballot, the presidential primary process for both major parties is essentially concluded.

Joe Biden is all but certain to be the Democratic Party’s nominee, while, despite Nikki Haley’s persistent efforts, Donald Trump is highly likely to secure the Republican Party’s nomination.

At first glance, this may appear perplexing. The Iowa caucuses and New Hampshire primary have only accounted for 61 out of the approximately 2,400 delegates who will officially vote for the GOP nominee at the party’s convention in six months.

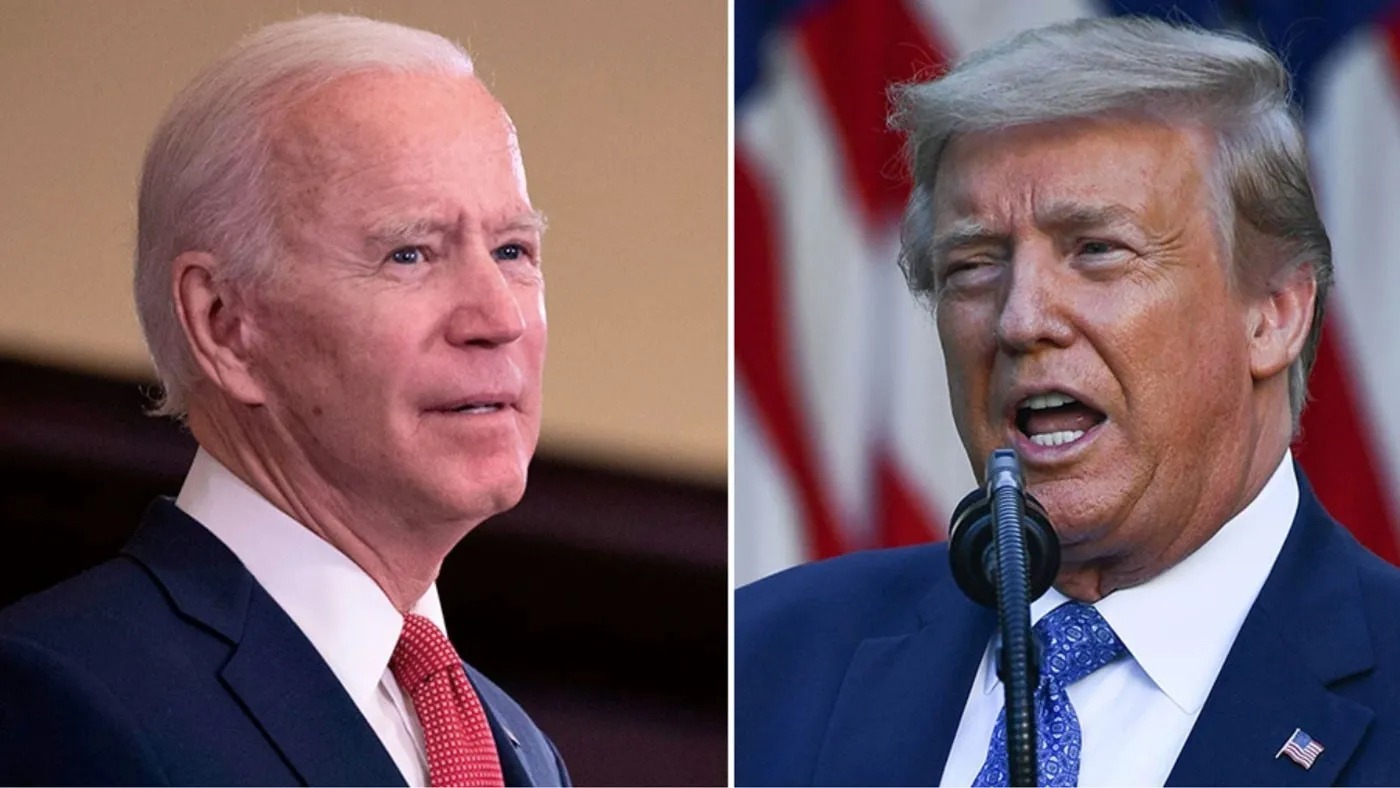

Stalemate between Trump and Biden (Credits: The Hill)

None of the Democratic Party’s over 4,000 delegates have been chosen yet. Moreover, these candidates don’t necessarily represent the preferences of a majority of Americans, as recent polls indicate dissatisfaction with both Biden and Trump.

However, the issue extends beyond the influence of a few states and the early locking in of candidate choices. The system, due to changes in party rules over the years, now practically precludes the possibility of launching a campaign after the start of the election year. This problem, which has been developing for some time, is particularly apparent in this election cycle.

The “frontloading” aspect of the delegate selection process further diminishes the democratic nature of the primary system. States aim to have maximum impact by scheduling their primaries as early as possible in the election year. Additionally, most states now enforce rules requiring candidates to register for a party’s primary by the first week of the election year.

Contrary to the expectations of those who crafted the delegate selection rules over five decades ago, the process has become less democratic. Back then, I played a role in drafting key aspects of the process that still govern how both major parties choose their presidential nominees.

The reform commission, led by the Democratic Party, sought to eliminate the “smoke-filled rooms” where party leaders could unilaterally select the nominee without voter input.

The rules, adopted in 1968, emphasized the need for an open process like a primary or caucus and specified that the selection must occur in the calendar year of the election, aiming for full public participation.